Can Disgust Predict Legal Decision-Making? An Experimental Jurisprudence Perspective on Gut Feelings and the Rule of Law

¿Puede el asco predecir la toma de decisiones jurídicas? Una perspectiva de jurisprudencia experimental sobre emociones viscerales y el Estado de Derecho

Can Disgust Predict Legal Decision-Making? An Experimental Jurisprudence Perspective on Gut Feelings and the Rule of Law

Isonomía. Revista de Teoría y Filosofía del Derecho, no. 61, 2024, pp. 279 -313

Received: 08 April 2023

Accepted: 23 september 2024

Abstract: In this article we consider whether the theory of moral reasoning developed by Jonathan Haidt can be usefully adapted to illuminate aspects of legal reasoning. According to Haidt’s social intuitionism, moral reasoning is incapable of controlling our moral intuitions. Moral reasoning is mostly just an ex post rationalisation of independently formed intuitions. But is control regained when we move from the moral to the legal domain? Are we able to control the application of legal rules, or are our legal judgments, like our moral judgments, the result of the distorting influence of intuitions? To explore this issue, we will attempt to develop and discuss an experimental protocol focusing on the role of disgust in rule-based decision making. We will attempt to illustrate a methodology that can illuminate the psychology of rule-following by discussing its theoretical and methodological premises.

Keywords: Jonathan Haidt, ex post rationalisation, rule of law, exclusionary reasons, disgust.

Resumen: En este artículo nos planteamos si la teoría del razonamiento moral desarrollada por Jonathan Haidt puede adaptarse de forma útil para iluminar aspectos del razonamiento jurídico. Según el intuicionismo social de Haidt, el razonamiento moral es incapaz de controlar nuestras intuiciones morales. El razonamiento moral no es más que una racionalización ex post de intuiciones formadas de forma independiente. Pero, ¿se recupera el control cuando pasamos del ámbito moral al jurídico? ¿Podemos controlar la aplicación de las normas jurídicas o más bien nuestros juicios jurídicos, al igual que nuestros juicios morales, son el resultado de la influencia distorsionadora de las intuiciones? Para explorar esta cuestión, intentaremos desarrollar y discutir un protocolo experimental centrado en el papel del asco en la toma de decisions basada en reglas. Intentaremos ilustrar una metodología que puede iluminar la psicología del seguimiento de reglas, discutiendo sus premisas teóricas y metodológicas.

Palabras clave: Jonathan Haidt, racionalización ex post , Estado de Derecho, razones excluyentes, asco.

I. Introduction

In this article 1 , we will consider whether the theory of moral reasoning developed by Jonathan Haidt can be usefully adapted to illuminate aspects of legal reasoning. According to the theory advocated by Haidt, social intuitionism, moral judgments are the result of unconscious intuitions that relegate conscious reasoning and our critical values to a marginal role. Reflective morality is unable to dominate unconscious morality. But is control regained when we move from the moral to the legal domain? Are we able to control the application of legal rules, or are our legal judgments as well as our moral judgments the result of the distortive influence of intuitions?

In exploring these issues, we will attempt to develop and discuss an experimental protocol, focused on the role of disgust in rule-based decision-making. The protocol we will discuss has been partially implemented by the two authors. Still, the purpose of this paper is not to discuss the results gathered so far – which will be occasionally mentioned with a merely illustrative purpose –, but rather to discuss the theoretical and methodological premises we have decided to adopt. The data we have collected do not yet provide a sufficient statistical basis for firm conclusions and will therefore be discussed in a separate article once the experimental study is complete. Nevertheless, it must be pointed out that all the considerations presented here are not the result of pure abstract speculation, but are based on the authors’ experience of putting the protocol to the test in seminars organised as part of a European project, involving the universities of Alicante, Bologna, Palermo, Maastricht, Ljubljana and Krakow, entitled RECOGNISE 2 .

The reader may find this paper to belong to an unusual literary genre. This is not strictly speaking an experimental paper, in which a thesis is supported or falsified through empirical data 3 . We do not directly tackle experimentally the classical jurisprudential question of whether judges are constrained by rules. We are rather interested in the conceptual and methodological question of how in principle this could be done. We believe that this is a separately interesting type of enquiry which should probably be more frequently pursued in the field of experimental jurisprudence. These are precisely the questions that should be the core of the subject as they are relevant both in psychology and in legal theory. We believe that looking for questions that are both testable and philosophically interesting builds a very useful bridge between psychology and legal theory.

If our research programme were to show that disgust unconsciously and systematically distorts legal reasoning, our confidence in the ability of decision-makers to respect the rule of law would be profoundly undermined. If this were the case, judges and jurors would oλen think that they are following legal rules while they actually are not. Whether or not the rule of law is an unattainable ideal cannot be determined by an abstract armchair discussion: it should be proven experimentally.

This empirical protocol, inspired by Haidt, is an attempt to shed light on the empirical nature of questions about the viability of the rule of law and on the psychology of rule-following.

The structure of the paper is as follows. In the second section, we introduce Haidt‘s social intuitionism. We will explain how this theory attacks the previous rationalist tradition in moral psychology by arguing that moral opinions do not arise from conscious reasoning, but rather from unconscious automatic processes. We will also explain how Haidt arrived at this conclusion. In the third section, we will show the potential relevance of Haidt’s theory for legal and, in particular, judicial decision-making. In the fourth section, we will briefly explain why we chose disgust as the focus of our empirical research. In the fiλh section, we will describe the experimental protocol. In the final section, we will explain some aspects of our methodology in order to answer some objections that might be raised.

II. Background: Jonathan Haidt’s social intuitionism

Two aspects of Johnathan Haidt’s work on moral psychology are relevant for our purposes: his moral foundations theory and his critique of the relevance of rational processes to moral judgement, a thesis associated with the previously dominant approach in the field, known as rationalism. Haidt’s experiments focused on the phenomenon of harmless but offensive behaviour (Haidt et al., 1993; Haidt, 2012, pp. 21 ff.). Haidt assumed a distinction between moral condemnation and merely conventional condemnation, according to which conventional norms, but not moral norms, are “arbitrary and changeable to some extent” (Haidt, 2012, p. 11) 4 . His purpose was to understand whether moral condemnation proper regards only the infliction of harm, the violation of rights, the inequality in the distribution of goods, or whether – to put it in Haidt’s words – “there is more to morality than harm and fairness”.

Here there is an example of what may count as a harmless but offensive conduct according to Haidt.

Julie and Mark are brother and sister. They are travelling together in France on summer vacation from college. One night they are staying alone in a cabin near the beach. They decide that it would be interesting and fun if they tried making love. At the very least it would be a new experience for each of them. Julie was already taking birth control pills, but Mark uses a condom too, just to be safe. They both enjoy making love, but they decide not to do it again. They keep that night as a special secret, which makes them feel even closer to each other (Haidt, 2001, p. 814).

Haidt’s experiments were based on hundreds of face-to-face interviews. In these interviews, Haidt and his colleagues asked people to make moral judgements about behaviour depicted in vignettes such as the one about Julie and Mark. Among other things, Haidt asked respondents (i) how they judged the depicted behaviour, (ii) what reasons they gave for their judgement, (iii) and whether the behaviour was such as to cause harm to a victim (see Haidt et al., 1993, p. 617). His results can be illustrated focusing on two different types of respondents: 1. the group of those who said that the behaviour was not harmful but was still immoral, and 2. the group of those who said that the behaviour was immoral because it was harmful 5 .

Let’s start with the former. In an intercultural experiment, Haidt and colleagues interviewed children aged between ten and twelve and adults from Brazil and the U.S., from different social classes. Many of the respondents said that the behaviour depicted in the vignettes was disturbing, but not harmful. Some, however, still condemned the behaviour. Haidt concluded that cultural and, above all, social differences have a significant impact on the tendency to perceive disturbing but non-harmful behaviour as a moral violation: in particular, people from disadvantaged social classes showed a tendency to adopt a morality that also sanctions harmless behaviour – a morality that is not based on harm. This tendency was even more pronounced among members of the Brazilian lower social classes than among members of the American lower social classes (Haidt et al., 1993) 6 . Haidt’s conclusion is that “There’s more to morality than harm and fairness” (Haidt, 2012, p. 114). He identifies six psychological sources or “foundations”, as he calls them, of moral judgment:

1) The care/harm foundation;

2) The fairness foundation (fairness as proportionality);

3) The liberty/oppression foundation;

4) The loyalty/betrayal foundation;

5) The authority/subversion foundation;

6) Sanctity/degradation foundation.

Haidt then used this framework to analyse the different moral psychologies of leλwing and right-wing people. In doing so, he found that WEIRD (White Educated Industrialised Rich Democratic) people tend to be influenced by only the first three foundations, but within WEIRD societies conservatives embrace a comparatively broader morality than progressives because sometimes they are affected by the remaining three foundations as well (Haidt, 2012, p. 129).

Let us now turn to the second interesting type of respondents: those who condemned the behaviour on moral grounds only because they considered it to be harmful. Although Haidt and his colleagues had tried to write stories in which the behaviour described was not harmful, some respondents still thought it was. Haidt’s idea was that these respondents were “inventing victims”. This conclusion may seem unjustified. Why not simply say that some people have a different conception of harm than that of Haidt and his colleagues? What would give Haidt reason to believe that people who found a harm in his vignettes were just “inventing victims”?

The main reason for ruling out that these people simply had a different conception of harm is how they reacted to objections. For example, on hearing the incest story (a story which is designed to shock but, in Haidt’s view, without depicting any harm), some claimed that Julie and Mark had engaged in harmful behaviour. When asked to identify what the harm was, they said that any children they might have could develop disease, or that Julie and Mark themselves might suffer psychological damage. At this point, the experimenters showed that the story ruled out these possibilities in the case under discussion. The participants accepted this observation, but were unwilling to revise their belief. In other words, when corrected, the respondents accepted the objections to their justifications, but did not change their original judgement, and remained speechless – dumbfounded. If their judgments genuinely depended on the considerations they offered to justify them, once these reasons were refuted we would expect the respondent to revise his or her judgment, or to say that he or she did not have a clear idea on the matter. Haidt calls this “moral dumbfounding”. He then built his whole theory of moral judgement on this idea (Haidt 2001, p. 815).

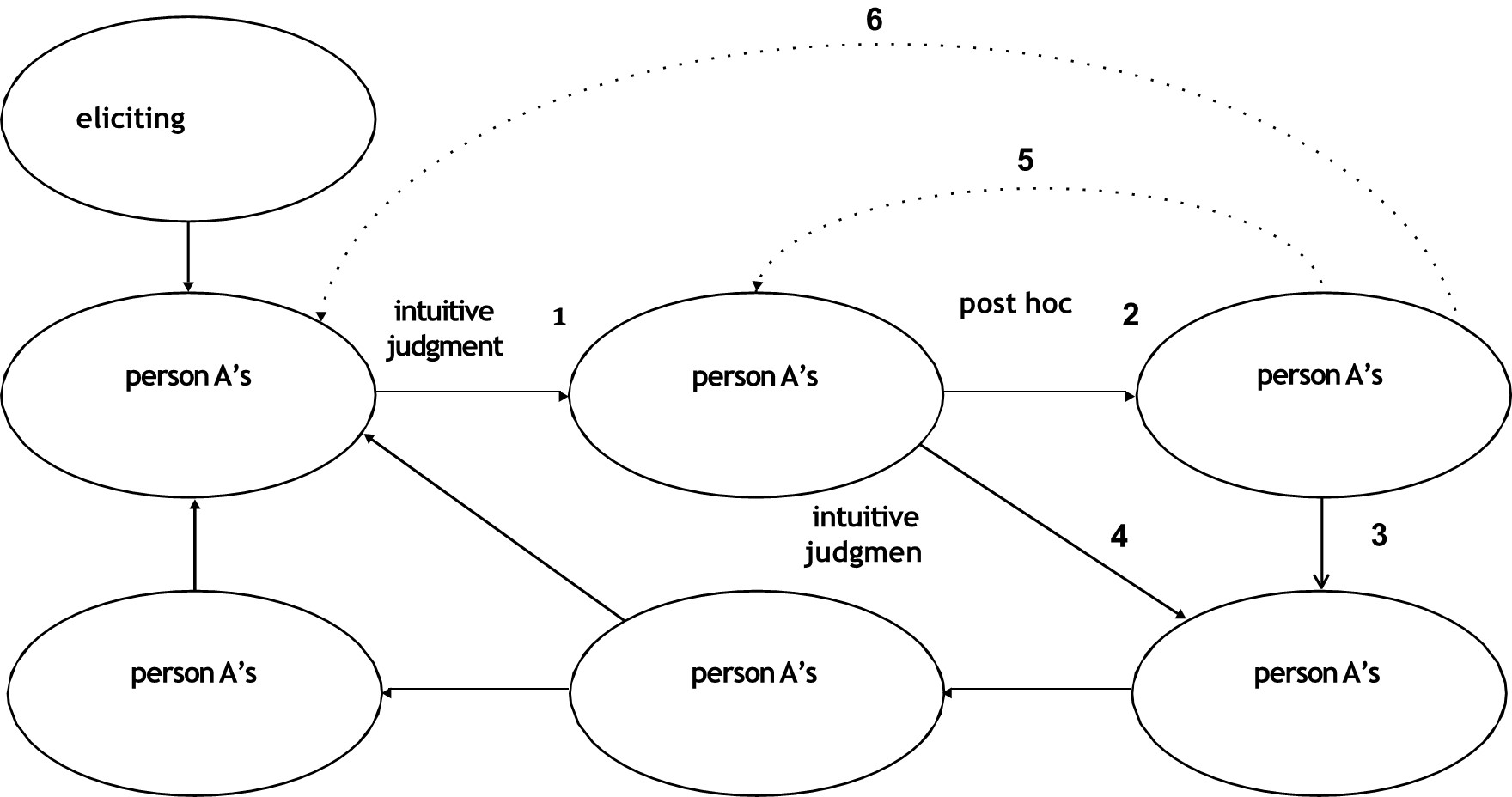

When faced with certain events, we oλen adopt our judgments intuitively, that is, rapidly and without being aware of the mental processes that lead to their formulation (arrow 1) 7 . Aλer adopting these judgments, we construct reasoning that supports them (arrow 2) 8 . Unlike the processes that led to the formulation of the judgement, the process of its justification is conscious. This is a process that cannot cause the judgement itself, because it follows it. We speak in this regard of reasoning as “ex post rationalisation”. But, as the image shows, the model goes beyond this. Arrows (3) and (4) account for the social, relational, component of moral judgment. Although reasoning at the individual level is used to confirm rather than revise our judgement, reasoning can also be used to change other people’s intuitions and thus their judgements (3). Moral arguments are oλen futile, because people very rarely change their mind on moral matters. However, in rare cases they do. In particular, Haidt hypothesises that “reasoned persuasion works not by providing logically compelling arguments, but by triggering new affectively valenced intuitions in the listener” (Haidt, 2001, p. 819). Furthermore, in order to get others to change their judgement, it is not even necessary to give reasons, it is enough to express one’s own position (4). We are social animals highly exposed to the influences of our peers, so that “the mere fact that friends, allies, and acquaintances have made a moral judgment exerts a direct influence on others, even if no reasoned persuasion is used” (Haidt, 2001, p. 819). Normally, then, we change our minds when exposed to others’ reasoning or simply to others’ opinions. In addition to that, Haidt acknowledges that, in some instances, individual thinking can modify our own initial intuitive judgments. This possibility is represented by arrows (5) and (6), which are represented with a dotted line. The meaning of the dotted line is that these are comparatively rare phenomena in a general account of how moral reasoning works. Haidt’s crucial point is expressed by arrows (1) and (2), and may be stated as follows: moral judgement is intuitive and not deductive, and it does not depend causally on the reasons by which we justify it.

Before moving on, it is important to avoid a possible misunderstanding. Haidt’s conclusion may be misinterpreted as a reassuring representation of human moral deliberation: in order to reach a sensible conclusion in practical matters, we do not even need to reason; we reach the conclusion intuitively, quickly, and without a great effort. In other words, we may look at our intuitions like a compressed file which contains all the effortful passages of moral reasoning. Moral intuition can be thought of as a form of heuristic, a shortcut allowing us to reach a good solution without going through the laborious and time-consuming process of reasoning 9 . We have been endowed by God, or we have evolved, with reactive dispositions to behave well in critical situations in which reasoning would be detrimental. This view may be ascribed to virtue ethics: “A virtue is an excellent trait of character. It is a disposition, well entrenched in its possessor—something that, as we say, goes all the way down, unlike a habit such as being a tea-drinker—to notice, expect, value, feel, desire, choose, act, and react in certain characteristic ways” (Hursthouse et al., 2022, 1.1).

According to psychologist and philosopher Joshua Greene, this view can also be found in Kant.

The categorical imperative prohibits masturbation because it involves using oneself as a means (…), and it just so happens that the categorical imperative’s chief proponent finds masturbation really, really disgusting (...). And so on. Kant, as a citizen of eighteenth-century Europe, has a ready explanation for these sorts of coincidences: God, in his infinite wisdom, endowed people with emotional dispositions designed to encourage them to behave in accordance with the moral law (Greene, 2007, p. 69)

Basing one’s moral judgements on intuitions and emotions not only has an instrumental advantage but may also be preferable for intrinsic reasons. Intuitions and emotions may be considered acceptable sources of moral judgements because they are able to produce rationally defensible judgements more quickly than rational thought, but also because they seem to represent our identity more authentically, sometimes more so than logic and argumentation. In a famous passage, Bernard Williams argued that at times it is undesirable that agents be moved by moral impartial principles rather than by attachments and direct concerns. Williams makes us imagine the case of a man who can either save a stranger or his wife, and who chooses to save the wife as the result of the application of an impartial general principle. According to Williams:

[T]his construction provides the agent with one thought too many: it might have been hoped by some (for instance, by his wife) that his motivating thought, fully spelled out, would be the thought that it was his wife, not that it was his wife and that in situations of this kind it is permissible to save one’s wife (Williams, 1981, p. 18).

The passage may be interpreted as saying that, in certain circumstances, it is inappropriate to resort to moral reasoning – the application of impartial moral principles – not because reasoning is slow and effortful, but because reasoning creates a sort of dehumanising detachment between ourselves and our deeds (see also Smith, 1994, pp. 75-76).

The reason why Haidt’s picture of practical reasoning is disturbing and not reassuring is that there may be a fracture, a mismatch between the moral foundations on which the judgement is based and the values, principles, ideals that are evoked at the moment of reasoning. The source of this fracture or tension in our moral system is due to the social context. It may be that in certain social contexts some moral foundations are less accepted than others. In such cases, the subject can be said to be under what we may call an argumentative pressure: the subject is constantly requested to defend his or her views against prevailing divergent opinions. The pressure is managed at the unconscious level: the point is not that we consciously – rhetorically and cynically – hide our moral foundations; instead, we hide them even to ourselves, and we end up believing to the socially accepted arguments we use to justify our judgments. Haidt’s subjects remain sincere 10 . One specific context – analysed by Haidt – which puts people under an argumentative pressure is that of U.S. colleges, where progressive ideology seems to be more common than conservative ideology (see for example Haidt et al., 2001, p. 214). But there are countless other contexts in which the same phenomenon can occur. This presumably includes the legal context.

III. Haidt’s theory and the law

An implicit assumption of everyday legal practice is that people are capable of acting and deciding on the basis of rules laid down in statutes, laws and regulations. Legal rules are supposed to give us reasons to act in a certain way that can prevail on what would otherwise guide our behaviour: our interests, our whims, as well as some of our moral intuitions. This assumption is part of the idea of the rule of law, and it is central to the concept of law as analysed in the work of some legal philosophers 11 .

A prominent analysis of the way in which legal rules bind our behaviour has been carried out by Joseph Raz. According to Raz, legal rules, and in general authoritative directives, as far as they are legitimate, replace the reasons that would otherwise apply to the case (Raz, 1986, p. 42). In his terminology, they function as “pre-emptive reasons”. More specifically, they are a conglomerate of two different types of reasons: a first-order reason in favour of an action, and a second-order reason of a particular kind which excludes other reasons against, or in favour of, that action. Qua second-order reasons, legal rules are exclusionary reasons. Consider the rule about stopping at a red traffic light. When the traffic light is red, there may be many possible reasons for not stopping. But it is the very purpose of the rule to make you refrain from acting on those possible reasons. According to Raz, under certain conditions, the exclusion of reasons is absolute: according to other authors, like Schauer (1991; see also Gur, 2018, p. 135 ff.), the exclusion is partial. Raz believes that the idea of exclusionary reasons explains the peculiar way in which legal rules prevail on other kinds of reason-giving standards. In his view “excluding” is very different from “overriding”. When we weigh up the pros and cons of doing something in our moral reasoning, we try to decide which reasons are stronger and should then override the weaker ones. But legal rules, Raz argues, are not added to other first-order reasons applying to the case (Raz, 1986, p. 46), and correlatively their prevalence doesn’t depend on their being stronger than these reasons. They do not override first-order reasons, rather they prevail on first order reasons by excluding them, in virtue of their structure or nature, in virtue of their being second-order reasons (Raz, 1990, p. 40). To take the example of the traffic light again: my reason for stopping at the light because it is red is not stronger than my reason for not stopping because I am late. Simply accepting the authority of the traffic light means accepting to do what the traffic light says, even if I would otherwise have done something else, for example, not to stop and run to the meeting I have to go to. The exclusion of reasons does not work in some cases. Rules made by legitimate authorities do not bind us if they are made outside the scope of the authority we attribute to them (Raz, 1990, p. 40), or possibly if the authority has clearly made a mistake (a case on which Raz declined to pass judgement – Raz, 1986, p. 62). But leaving aside these cases, law makes some first-order reasons absolutely irrelevant, to the extent that a rule established by a legitimate authority must be followed even when the authority made a great (though not clear) mistake in issuing that rule.

Schauer accepts that the function of rules is that of providing exclusionary reasons, but in his view exclusion is not necessarily absolute. He gives the example of an individual who adopts the personal rule of only going on holiday to France and ignoring all offers, even very cheap ones, to go to other countries. We would say that this individual is still following this rule, even though he or she decides to go to Austria whenever confronted with not just a good but an exceptional offer. According to this model, a rule remains in place even if the agent is guided by the rule most of the time, or in normal situations, while sometimes, or in abnormal situations, he or she is guided by first-order reasons (Schauer, 1991, pp. 88 ff.).

For both Raz and Schauer, still, rules have in other words a mediating role“between deeper-level considerations and concrete decisions” (Raz, 1986, p. 58). In this sense, law gives us reasons to refrain from acting on the merits of the case. The merits are, of course, crucial, and arguably – this is the position Raz takes – the authority of law does depend on them, authority does depend on first-order reasons (this is an essential premise of the service conception of authority, Raz, 1986, ch. 3). But once the law is formulated and has authority over us, it forbids us to act on the basis of our personal examination and understanding of the first-order reasons concerning the concrete case. According to Raz (1986, p. 47): “The whole point and purpose of authorities (…) is to pre-empt individual judgment on the merits of a case, and this will not be achieved if, in order to establish whether the authoritative determination is binding, individuals have to rely on their own judgment of the merits”.

Legal reasoning involves, then, special justificatory constraints: accepting the authority of law means accepting that certain factors are excluded from consideration and deemed irrelevant. It is no coincidence that a traditional way of representing justice is as a blindfolded goddess. But are we really able to blind ourselves and ignore legally irrelevant factors in this way? Can we really switch off our moral brain and activate our legal brain at will, as the legal tradition seems to suggest? An experiment inspired by Haidt’s methodology could help to answer these questions. For example, if it could be shown that factors that are legally irrelevant but likely to evoke disgust systematically influence judgments about whether or not a legal rule has been violated, this would indicate that in these cases the exclusionary function of rules is not realised in practice. Subjects may not be able to submit to the authority of rules in the way that Raz’s theory claims they should. Haidt’s research revealed some of the psychological flaws and distortions that plague moral reasoning. In the moral domain, people believe they are responding to certain reasons, when in fact they are decisively influenced by unconscious factors. We think it would be interesting to test whether legal reasoning is immune to these distortions. And we think it’s possible to test this hypothesis using a version of Haidt’s methodology.

As we mentioned, legal reasoning seems like a perfect field of study for developing Haidt’s theory. Haidt looked for moral dumbfounding in social contexts where agents have moral intuitions that conflict with the arguments they are socially allowed to make. Specifically, he studied how subjects with conservative moral intuitions might struggle to justify their condemnation of certain behaviour in the context of American college discourse, where an ethics of autonomy (roughly a liberal, progressive, ideology) prevails. The justificatory constraints created by the social environment produce a mismatch between what the subjects feel is right or wrong, and what subjects genuinely think is the correct way to justify the claim that it is right or wrong. But the justificatory constraints produced by American college discourse are nothing compared to those of legal discourse. Law is the domain par excellence in which some practical arguments are forbidden. The very point of having legal rules in place is that their existence will make irrelevant otherwise relevant arguments.

The importance of the experiment is obvious when we consider what the proof of the hypothesis would suggest. It would be evidence that one of the crucial mechanisms of legal decision making and of the rule of law is hampered by the very psychological functioning of our practical reasoning 12 .

Probably the most enduring debate in the philosophy of law is that concerning the relationship between law and morality 13 . What we would like to suggest here is that one important aspect of this debate should be disputed on the basis of empirical data. If it were proved that our cognitive faculties do not allow us to exclude legally distorting factors and that inevitably our moral intuitions penetrate legal reasoning, at least a positivist image of legal reasoning would possibly be undermined, but so would be a natural law conception of legality. Those who believe there is a connection between law and morality still assume that interpreters are able to act based on their conscious morality. That is, they are able to say which moral reasons they are taking to be legally relevant. The success of experiments of the kind we propose here would also challenge this rationalist presupposition on which natural lawyers draw.

In short, it is pretty clear to us that if legal reasoning were affected by the same psychological phenomena that Haidt describes in moral reasoning, this would have dramatic consequences for our conception of law. But if the opposite were the case, this would also be of extreme interest. If this were the case, one could build an argument based on the following modus tollens.

Major premise: If legal reasoning were a type of moral reasoning, it could be subsumed under the scheme proposed by Haidt (i.e., roughly, in morally relevant cases, it would tend to be a form of ex post rationalisation).

Minor premise: Legal reasoning cannot be subsumed into the scheme proposed by Haidt.

Conclusion: Legal reasoning is not a type of moral reasoning

Are personal moral judgements and legalistic applications of rules two different psychological natural kinds? If we could show experimentally that, when we are applying legal rules, we are indeed able to switch off our moral brain and activate our legal brain, a question may arise as to what factors can make this possible. Is this ability affected by legal expertise? And if so, in which sense? Are trained jurists especially prone to bend rules to fit their moral intuitions or rather are they more inclined to some kind of legalistic detachment and moral disengagement? We think this may be an extremely promising line of research for experimental jurisprudence.

The successful outcome of this experiment would be of particular relevance for criminal law. In criminal law, not only the rule of law but also the harm principle applies: a judge or jury should only convict the defendant where the crime harmed or put into danger a legal good (Manes, 2005). But if our hypothesis were to be confirmed, this would show that there is a risk of the judge or jury seeing harm even where there is none. This would allow us to read in a new light a problem typical of certain arguments in criminal law, i.e., arguments that refer to evanescent legal goods 14 . An example of this kind of reasoning can be drawn from Italian constitutional case law: a famous Constitutional Court ruling on incest (Corte Cost. 518/2000). In this case, the Court is called upon to judge the constitutional legitimacy of incest in the light of the harm principle (prίνcίpίο dί οffeνsίvίsà) and rejects the thesis of constitutional illegitimacy by identifying the protected good in a particularly unsatisfactory manner. Why does the legislature punish incest even in cases where there is no offspring and therefore no risk of the conduct generating genetic diseases in children? According to the court, because the function of the offence of incest is not the protection of a “eugenic” good but to avoid “disruptions of family life” (“perturbazioni della vita familiare”) 15 . But what exactly does “disruption of family life” mean? To what disruptions is the Court referring? What data does it rely on to say that these disruptions would occur? An application of Haidt’s research to legal reasoning would suggest that in such cases judges are simply struck by their feeling of disgust and having no rational argument to justify their decision they simply make up a non-existent harm.

IV. Why disgust?

As we mentioned, the experiment discussed in this article focuses on disgust. It is now appropriate to explain the reasons behind this choice and, even before that, to explain what we mean by the word “disgust”. Disgust is a complex emotion that has evolved to serve several functions in humans. One model, developed by Rozin, Haidt and colleagues (Rozin et al., 2008), suggests that there are four domains of disgust: core disgust (which involves the rejection of harmful substances), animal reminder disgust (which helps quell anxieties about our animal nature), interpersonal disgust (which protects the social order), and socio-moral disgust (which helps maintain group cohesiveness). Another model, proposed by Tybur and colleagues (Tybur et al., 2013), suggests that disgust has evolved to solve three different problems caused by pathogenic microorganisms: pathogen disgust helps us avoid eating or touching contaminated substances; sexual disgust helps us avoid selecting sexual partners who may produce unhealthy offspring; and moral disgust motivates us to avoid interactions with individuals who may be harmful to ourselves or our social network. According to yet another view, “the mind computes expected values of consumption, contact, and sex to regulate personal decisions regarding what to eat, what to touch, and with whom to have sex” (Patrick et al., 2018, p. 124). Something that all these views have in common is the idea that disgust is a form of protection from a threat of contamination associated with an impulse to exclude or flee from what is seen as a dangerous or infectious factor. Also, from a behavioural point of view, disgust is normally associated with a withdrawal or avoidance of the object, event, or situation that is causing it. This clearly makes disgust the basis to many of our intuitions about what we should do in a vast number of situations. Disgust, as a moral emotion, is related to the human ability to form alliances and cooperate with others in pursuit of a common goal, and to the principles of sexual selection in which males compete for access to resources in order to attract females for reproduction.

If our experiment showed that decision-makers tend to be guided by moral intuitions about equality or authority when applying legal norms, this would not necessarily be surprising or prove the existence of a phenomenon of ex post rationalisation of unconscious emotions. This is because in contemporary constitutional democracies, it is considered perfectly legitimate to be guided by values that are constitutionally binding. A canonical technique of interpretation is that of attributing relevance to considerations based on constitutional values that are not expressly mentioned in the provision to be interpreted. This is done in order to select from among the linguistically possible interpretations only those that would avoid conflict with the Constitution and preserve the legitimacy of the provision being interpreted. And in the constitutions of contemporary legal systems one can find values and principles traceable to almost all moral foundations: care/harm (e.g. the harm principle in criminal law); fairness/ cheating (e.g. the principle of equality, reasonableness); liberty/oppression (e.g. civil rights and liberties); authority/subversion (e.g. the principle of legality; public order), loyalty/betrayal (e.g., the fidelity to the Nation, the State or the Republic oλen invoked in Constitutions). But the foundation of sanctity and degradation seems to constitute an exception. A legal judgement influenced by disgust is therefore more likely to be the effect of an unconscious mechanism than one influenced by the values represented in liberal constitutions, which, according to prevailing normative theories of interpretation, should guide all legal judgements anyway 16 .

What makes considerations based on disgust and purity plausibly less compatible with Western constitutional culture than those based on harm, equality, authority, etc.? This issue can be illustrated with reference to a book by Martha Nussbaum (2004) titled Kίdίνg Pοm Kumaνίsy. Nussbaum distinguishes two ways in which a legal decision maker might consider the repulsive nature of a behaviour as pertinent in deeming it unlawful. First, the mere fact that an action is disgusting can be viewed as harming those whose senses are exposed to it and experience disgust as a result. In this case, conduct becomes reprehensible only if there is someone who observes it and suffers an unpleasant experience as a result. Being exposed to the stench of an overflowing toilet is an example of disgust as harm. The act of harming someone by disgusting them is sanctioned in common law systems by, for example, nuisance laws. (Nussbaum, 2004, p. 158 ff.). Alternatively, disgust can be seen as a symptom that the action provoking it is morally impure or degenerate and should be avoided regardless of anyone has directly suffered harm from witnessing it (Nussbaum, 2004, p. 86, p. 103, pp. 125 ff.). Disgust is, in this second case, an epistemic tool, a form of moral alarm. From this perspective, disgusting behaviour is forbidden not because of the harm it causes by disgusting someone, but because of another kind of harm that we are supposed to be able to recognise in it unconsciously. It is this unconscious recognition that is regarded as the cause of our feeling of disgust. This second form of disgust does not depend on sensory stimulation. Rather the person feels disgust just by entertaining the thought of an otherwise harmless action that the person considers immoral. One of Nussbaum’s examples is the disgust some conservatives feel at the thought of gay sex: “it is offense occasioned by imagining what is going on” (Nussbaum, 2004, p. 126). This is what she calls disgust “in merely constructive sense”.

Nussbaum does not think that emotions in general cannot or should not guide legal decision makers in their judgments. There are emotions, such as anger or fear, which, according to Nussbaum, although at times misguided, can oλen provide some helpful guidance in practical matters. For example, anger and indignation are oλen responses to unjust harm done to vulnerable people. Disgust, on the other hand, is “typically unreasonable, embodying magical ideas of contamination, and impossible aspirations to purity, immortality, and nonanimality, that are just not in line with human life as we know it” (Nussbaum, 2004, p. 14). Thus, according to Nussbaum, merely constructive disgust is not an occasionally misleading emotion, but one that is always problematic and can never provide a reasonable basis for criminalising behaviour or otherwise making legal judgments (Nussbaum, 2004, pp. 13-14). In short, while the liberal legal tradition may accept the legal relevance of disgust as harm, it, from John Stuart Mill onwards, traditionally rejects the idea that disgust can be a guide for the identification of impure and therefore unlawful behaviour. This rejection reflects the prevailing attitude in the West regarding the argumentative relevance of disgust, which has led to the exclusion of references to purity and degradation from our constitutions. Nussbaum’s argument is normative: she critiques the irrationality of disgust, arguing that it is oλen rooted in cultural biases and magical thinking about contamination. We do not take any stance on this normative argument, but we merely want to use it as an example of the cultural tendency that has delegitimized explicit reference to disgust in legal reasoning in the West.

We do not even need to assume, on the descriptive level, that disgust can never play any useful role in the legal reasoning. Some conservative lawyers may indeed believe that disgust can signal immoral activities which for this reason should be criminalised (see Nussbaum, 2004, pp. 75-86) and even in liberal constitutional systems there may be moralistic provisions that reflect these points of view. Moreover, as we have seen following Nussbaum, there is the case of nuisance law, where disgust becomes legally relevant as a source of harm. In both cases, it might be argued, disgust is a conscious presupposition of the application of the rule, and then subjects cannot be said to be deviating from the application of the rule as a result of being disgusted. However, in the experiment we propose, respondents are asked neither to apply moralistic provisions nor nuisance law. Moreover, the viability of the experiment does not rest on the assumption that outside those domains people never mention disgust when it comes to justify the application of the legal rule. They sometimes do. We simply bet that disgust is a promising emotion to prove our hypothesis. We believe that, in WEIRD societies 17 , disgust holds more promise than other emotions for producing detectable unconscious effects on decision makers. From our perspective, the moral questions of whether disgust is an appropriate parameter for decision making, and the legal question of whether disgust is an appropriate parameter for identifying the content of legal norms, are both irrelevant. We do not intend to show that subjects influenced by disgust make a mistake on the basis of critical morality or on the basis of law, but simply that they make a mistake on the basis of what they themselves, in their conscious reasoning, consider to be the appropriate legal reasons for a decision.

V. Experimental Protocol

The problem we would like to examine through our experiment is the following: is the way in which we reach conclusions in legal reasoning mirrored by the arguments we put forward to justify them? Our general hypothesis is that it is not. We believe that legal reasoning can be subsumed within the explanatory schema of practical reasoning proposed by Jonathan Haidt. If this were the case, many legal arguments could be shown to be only ex post rationalisations of opinions formed through unconscious processes. To test this hypothesis, we propose an experiment in which two groups of subjects are presented with two questionnaires presenting two different versions of an identical legal issue. The two versions differ merely for the presence or absence of disgusting elements in the description of the conduct. All other legally relevant characteristics must be kept constant in both versions. The experimental group is asked to decide on the disgusting cases, the control group is asked to decide the non-disgusting ones 18 . Both groups are then asked to provide legal arguments in favour of their judgments. Whether the elements added in the stories presented to the experimental group are disgusting will have to be proven separately with different subjects, who will be given both versions of the cases and will be asked to rate how and how strongly they felt disgusted by the behaviour described in the story, by the person performing the behaviour, or by the story itself.

We will now present, by way of example, the four pairs of cases that we have used so far, but the methodology we are describing here could naturally also be applied using very different stories. We had law students of different nationalities as subjects. They were from the universities involved in the RECOGNISE project. Given that the subjects belonged to very different legal backgrounds, we decided to ask them to simply apply the legal rule mentioned in the case without considering any other rules from their own legal system. This instruction was intended to avoid as much as possible that the subjects could invoke in favour of their conclusions rules that could indirectly give relevance to the disgusting nature of the case.

The first case involves a surgeon who is accused of performing an unnecessary mastectomy. But while in one version of the questionnaire the subject is described as an extremely cautious practitioner who wants to avoid being sued by the patient if the cancer degenerates, in the second he is a fetishist who derives sexual satisfaction from the act of operating on young and attractive patients.

Surgeon Control group

Frank, an elderly and experienced surgeon was ordered to pay a million-dollar compensation for operating too late on a woman with breast cancer who had died as a result of that delay. This experience has profoundly influenced Frank’s way of dealing with breast cancer cases. He usually opts for mastectomy in cases where other doctors would wait and choose other, less invasive, measures first. Yet, his colleagues on the whole justify his choices because very oλen they are the most prudent way to deal with the types of cancer he treats. A former patient of Frank’s learns from a friend about the trial she underwent and the policy he adopted as result. As she particularly suffered psychologically and physically from the mastectomy, she sues Frank for assault (“Whoever causes serious bodily harm to another person without his or her consent shall be punished by imprisonment of three to six years”). Should the surgeon be punished?

Surgeon Experimental group

Frank, an elderly and experienced surgeon, derives sexual pleasure from cutting the flesh of young female patients. When he has to deal with young, attractive women he usually opts for mastectomy even in situations where other doctors would wait and choose other, less invasive, measures first. However, his colleagues on the whole justify his choices because they are very oλen the most prudent way to deal with the types of cancer Frank deals with. Patients in general say they are satisfied with Frank’s performance. One day the surgeon tells the story of his fetish in a web forum. A woman recognises herself in one of the stories told. Because she has particularly suffered psychologically and physically from the mastectomy, she sues Frank for assault (“Whoever causes serious bodily harm to another person without his or her consent shall be punished by imprisonment for three to six years.”). Should the surgeon be punished?

Note that the rule that subjects are asked to apply to both cases makes the circumstances or psychological motivations that lead to harm irrelevant, the only justifications that matter are seemingly those related to the formation and expression of “consent”. In neither case is the surgeon’s intention benevolent, and in both cases it is selfish. In both cases the motivation for the behaviour is linked to something very personal on the part of the surgeon, in one case fear due to past experience, in the other sexual interest.

The second case concerns euthanasia. It is about someone who helps a sick person to die in exchange for something. In one case the subject asks for a luxury car in exchange, in the other they ask to be able to cannibalise the body of the sick person.

Euthanasia Control group

Sophie suffers from a painful and incurable disease and asks Rick to kill her. Rick accepts, provided that he is then allowed to keep Sophie’s luxury car. Sophie accepts this condition. When Rick is caught, a problem arises on whether he committed a murder or a much less serious crime “homicide of the consenting person”, because it is unclear whether anyone can ever sanely consent to such an arrangement, and then whether Sophie was capable to make an informed decision. Should Rick be charged with murder?

Euthanasia Experimental group

Sophie suffers from a painful and incurable disease and asks Rick to kill her. Rick agrees, on the condition that he can then butcher Sophie’s corpse and eat it. Sophie accepts this condition. When Rick is caught, a problem arises on whether he committed a murder or a much less serious crime “homicide of the consenting person”, because it is unclear whether anyone can ever sanely consent to such an arrangement, and then whether Sophie was capable to make an informed decision. Should Rick be charged with murder?

In this case too the only relevant factor is the consent of the victim. In neither of the two cases is the reason behind the action altruistic, and in neither it is relevant.

The third is the case of a son who takes revenge on his mother by giving her one thing to eat instead of another. In none of the cases does she notice anything. In one case it is a food that the mother finds disgusting, seafood, in the other it is a food that the reader is likely to find disgusting, worms and insects.

Soup Control group

Robert looks aλer his old, blind and disabled mother. The son resents his mother because he believes she should bequeath more to him and less to his sister Anna. Out of rage, he decides to feed her seafood, for an extended period of time, passing it off as pasta in broth. The mother has always found seafood disgusting, but now she does not notice anything and does not suffer any negative health consequences. When Anna hears about this, she sues her brother on her mother’s behalf for damages. Should Robert be condemned to pay compensation?

Soup Experimental group

Robert looks aλer his old, blind and disabled mother. The son resents his mother because he believes she should bequeath more to him and less to his sister Anna. Out of rage, he decides to feed her flour worms and various insects, for an extended period of time, passing them off as pasta in broth. The mother does not notice anything and does not suffer any negative health consequences. When Anna hears about this, she sues her brother on her mother’s behalf for damages. Should Robert be condemned to pay compensation?

In none of the two cases the food proves to be harmful, which is the only relevant factor. In both cases it is only disgusting for someone, in one case the mother, in the other case the reader.

The fourth and last of the legal cases concerns a senior man who suffers health damage due to a conduct that, if judged dangerous, would exclude the right to be compensated by the insurance company. But in one case the activity consists of going on a mountain hike, in the other it consists of using a sex toy.

Insurance Control group

Albert, a 65-year-old man, is caught in a blizzard while hiking in the mountains. He manages to call for aid and he is rescued. Due to hypothermia doctors are required to amputate all the toes of his feet. Albert has paid for a health insurance according to which “medical expenses are covered as far as the state of need has not been provoked by a dangerous activity knowingly carried out”. Can Albert be denied compensation by the insurance company? 19

Insurance Experimental group

Albert, a 65-year-old man, inserts a long dildo into his rectum, as he oλen does while masturbating. The dildo, however, is pushed too far and remains stuck in his colon. Aλer having tried less invasive measures, his doctors decide that Albert needs to be urgently operated. The operation will consist in removing a portion of the man’s colon to extract the dildo. Albert has subscribed a health insurance according to which “medical expenses are covered as far as the state of need has not been provoked by a dangerous activity knowingly carried out”. Can Albert be denied compensation by the insurance company?

While subjects have no additional reasons for considering the second conduct more dangerous than the first, it arguably is more likely that some subjects will find the story disgusting in the experimental group rather than the control group. Both Alberts are portrayed as familiar with the activities they carry out, most of which are presumably not dangerous.

The questionnaire we use for the experiment also contains some of the original cases used by Haidt. These are presented both to the control group and the experimental group afier the set of questions requesting to apply legal rules. Here are the cases.

Jennifer works in a hospital pathology lab. She is a vegetarian for moral reasons— she thinks it’s wrong to kill animals. But one night she has to incinerate a fresh human corpse, and she thinks it’s a waste to throw away perfectly edible flesh. So, she cuts off a piece of flesh and takes it home. Then she cooks it and eats it. Was it wrong for the woman to do this?

Has Jennifer harmed someone with her conduct?

A man goes to the supermarket once a week and buys a chicken. But before cooking the chicken, he has sexual intercourse with it. Then he cooks it and eats it. Was it wrong for the man to do this?

Has the man harmed someone with his conduct?

A family’s dog was killed by a car in front of their house. They had heard that dogmeat was delicious, so they cut up the dog’s body and ate it for dinner. Was it wrong for them to do this?

Has the family harmed someone with its conduct? 20

We believe that our hypotheses will be confirmed if people who condemn conducts in this last set of moral cases (people who are affected by disgust in the moral domain) tend to condemn more in the legal cases of the experimental group. Finally, as already mentioned, subjects are asked to provide a brief justification for their previous answers. The purpose of this is to verify that subjects who have condemned do so for reasons other than being disgusted. There being a harm is the most plausible candidate explanation (hence the specific question asking on whether the subject believes the conduct is harmful) 21 .

VI. Objections and comments

To conclude, we present some considerations aimed at anticipating concerns and objections that could be raised against the design of this experiment.

A. Why would it be reasonable to assume that it is disgust and not another factor that influences judgement?

The main purpose of the experiment is to show that a subject who feels disgust towards a person or behaviour is more likely to condemn that person or behaviour when asked to make a legal judgement. Suppose that the subjects we exposed to cases designed to be disgusting actually showed a greater tendency to make judgments of condemnation than those we exposed to cases designed to be non-disgusting. How can we be reasonably sure that this difference in judgement is due to the fact that the subjects in the experimental group were actually more disgusted than those in the control group, and not due to some other factor? In other words, if we change the story to make it disgusting, the new elements of the story may produce a different judgement that is not motivated by their being disgusting. A simple way to minimise the risk indicated by this objection is to ask a group of people who are not involved in the actual experiment, but who are similar to the participants in socio-demographic terms, to rate the cases on a Likert scale, indicating how disgusting they find the person involved or the behaviour described in the case. This should assure us that the cases are indeed different in this respect: that the cases in the experimental group are indeed considered more disgusting than those in the control group. Although this does not, strictly speaking, prove that this is the only difference between the two groups of cases, it is reasonable to think that this is the relevant difference, as there is no commonality (other than the fact of inducing disgust) between the differential features characterising the cases submitted to the experimental group.

Moreover, if mainly the subjects who are more sensitive to disgust in the moral questions (the questions we borrowed from Johanthan Haidt’s experiments, see the end of par. V) were to condemn in the legal cases, this would be evidence that it was the disgust that made the difference and not other details. However, we could prove the legal equivalence of the twin cases independently. One idea would be to have them compared and rated by selected third parties that 1) show low sensitivity to the sanctity and degradation moral foundation, 2) are experts in law 22 .

B. Why do you think that the disgusting nature of the conduct is obviously legally irrelevant?

One can concede that the difference between the experimental group and the control group cases is that the former are more disgusting than the latter, but deny the fact that the two groups treat the two cases differently as a result is problematic. So, do we assume that disgust is legally irrelevant? No, as we said we want to remain neutral as to which interpretative approaches are legally correct and which are not. Part of the purpose of this experiment is to highlight a problem for the rule of law. The fact that mechanisms beyond the control of the decision-maker end up determining the outcome of the decision rather than the rules. If we are right, at least in some cases, decision-makers think they are guided by rules in making their judgments, but they are not. They arrive at their decisions independently of the rules and use the rules only to justify the decision, to rationalise it ex post. This leads to a reformulation of our problem. How can we rule out the possibility that the subjects in the experimental group genuinely and consciously believe that the protagonist of the story should be sanctioned precisely because of the disgusting features of his behaviour? That is, what if they consciously regard the rule as sanctioning the disgusting nature of the behaviour?

Well, we do not exclude this possibility at all. The main function of the section of the questionnaire in which subjects are asked to justify their judgments is precisely to check whether the characteristics that differentiate the cases submitted in the two groups are in fact considered legally relevant by the respondents. Our hypothesis will only be confirmed if three conditions obtain:

1) the experimental group decides more frequently against the protagonists of the cases than the control group;

2) the subjects in the experimental group do not justify their unfavourable judgments with arguments that are based on the elements that differentiate the cases they judge from the cases judged by the control group;

3) vice versa, the subjects in the control group do not justify their favourable judgments with arguments that are based on the elements that distinguish the cases they judge from the cases judged by the experimental group.

In informally testing this experimental protocol, we found, for example, that 73,7% of the subjects belonging to the experimental group decided for conviction in the Surgeon case, while in the control group only 47,6% did. If we look at the justification offered by the members of the control group, they do not mention the sexual motivation of the conduct, but only the fact that the surgeon has harmed the patient, the fact that he had to choose less invasive measures, the fact that he violated the patient’s consent, the fact that in choosing whether or not to operate he has been pushed by an egoistic concern. These reasons – valid or not – would have been just as compelling for condemning the surgeon in the non-disgusting version of the story.

C. Can disgust-driven rule application be evidence that the rule of law is being violated?

Suppose we have shown that if a judge finds a behaviour or a person disgusting, he or she is more likely to take unfavourable legal decisions against that behaviour or person. This is just a brute fact 23 . Does this prove that the judge is not correctly following the rules he or she is using to justify his or her decision? It might be argued that this conclusion implies a violation of Hume’s law, an inappropriate shiλ from is to ought. The causal effect of disgust on a subject’s judgement belongs to the realm of is (how the subject does apply the rules), and not to the realm of ought (how the subject ought to apply the rules). In order to show that the phenomenon of ex post rationalisation of disgust in legal judgments is a problem for the rule of law, we would have to show that it leads to a likely violation of rules. Prima facie, however, it is not possible to show that a behaviour leads to the violation of rules on the basis of the purely descriptive statements that constitute the results of our proposed experiment. Criticism along these lines is oλen directed at the strand of literature in experimental philosophy that relies on so-called debunking arguments, arguments that purport to reject an opinion on the basis of causal considerations about the cognitive process that produced it. It is certainly not the aim of this article to refute this type of criticism conclusively. We will limit ourselves to a few considerations.

The structure of a debunking argument is as follows. An agent supports a belief B on the basis of reason R. However, there is evidence that the formation of B is determined by causal factor C, totally independent of R 24 . C is independent from R in the sense that the facts that are adduced as a reason for the belief can exist without the facts causing the belief and vice versa (and that the obtaining of the former does not make the obtaining of latter more likely) 25 . This critique of epistemic justification can turn into a moral or legal critique if the proposition being critiqued has moral or legal content 26 . This is a kind of argument that starts with factual considerations and ends with a normative conclusion concerning the epistemic justification of a belief. However, one could argue that this does not necessarily constitute a violation of Hume’s law. Whether it does or not depends on the premises we can contextually rely on, adding them to the factual finding on which the argument is based. If we can base this argument on a reasonably acceptable normative background assumption, Hume’s law can be respected (Greene, 2014, pp. 711-714) 27 . A possible formulation of this assumption, applicable to our experiments, could be the following:

My meta-belief MB that reason R supports belief B is unjustified if I realise that the process of acquisition of MB is unreliable. The process is unreliable if I could have acquired MB by a causal factor C independent of R. If MB is unjustified, B is also unjustified.

An example may illustrate this. Suppose I hear the whistle of a train, and for this reason convince myself that I am near an old-fashioned railway station. It would be reasonable for me to abandon this belief, or at least to doubt its justification, if I discovered that I very oλen suffer from a strange type of tinnitus and hear train-like whistles independently of the fact that there are trains whistling 28 . Let us try to clarify in what respects these two apparently very different situations can be epistemically analogous. In both cases, there is an epistemically unreliable belief: in one case it is the belief that there is a train station nearby, and in another that the application requirements of a rule have obtained (e.g., the belief that a certain subject has de facto suffered certain consequences in eating a soup and/or that de iure these consequences constitute a “damage” for the purpose of law). The reason why the belief seems to be unreliable is that its formation is decisively (Nichols, 2014, p. 731, footnote 11) related to a causal factor that has no explainable relation with its object. The mere fact that the subject suffers from tinnitus (a circumstance causally unrelated to the presence of trains) makes him believe that he is in the vicinity of a railway station; the mere fact that the subject is disgusted (a circumstance causally unrelated to the violation of legal rules) makes him believe that a legal rule has been violated.

The shiλ from the descriptive to the normative level (from describing what caused a belief to criticizing it as unjustified) consists in stressing the lack of a non-accidental relationship between the truth of the belief and some causal factors that were decisive in determining the belief.

At this point, while some may accept that this kind of debunking argument scheme is justified in general, they may doubt that it is applicable in the specific case we are interested in. Paradoxically, the data collected could even be compatible with a hypothesis opposite to the one we originally formulated, i.e., that the disgust felt by the subjects does not distort their reasoning, but on the contrary makes it more likely that they apply the law correctly 29 . It could be hypothesized, for example, that the feeling of disgust experienced by the subjects of the experimental group leads them to pay greater attention to the details of the case and that the difference between their judgment and that of the control group is due solely to this: if we are disgusted, we are better at applying the law! 30 Alternatively, and more plausibly, one could argue that we simply do not know how disgust affects the legal correctness of decision-making. The hypothesis that disgusted people apply the law better at first sight explains the discrepancy in judgements between the experimental and control groups just as well as the opposite hypothesis that they are more likely to misapply it. Without normative premises about how the law ought to be interpreted, we should suspend judgement about which of the two explanations we prefer.

Could it not be that for some unknown reason there is a non-random correlation between the fact that a behaviour is illegal and the fact that that behaviour generates disgust? We cannot rule out this possibility, but we put forward two tentative answers. First of all, the unreliable nature of the disgust-driven reasoning would be particularly corroborated if our experiment were to reveal, as happened in the cases proposed by Haidt, a tendency for subjects to justify their conviction by making false assumptions (i.e., inventing facts not present in the proposed case or ignoring facts that are present). For example, in Haidt’s incest story, the respondents argue that the there is a danger that the girl will become pregnant, despite the story said that the two siblings were using contraceptive methods. Similarly, if our respondents in the Soup story would argue that the son poisoned the mother, this argument would be incompatible with the story which says that the mother did not suffer any health consequence. It would be hard to imagine how disgust could have worked as a heuristic for good arguments, if these arguments are based on false beliefs.

Other arguments may be less easily debunkable. Considering the Euthanasia story, imagine that respondents find the validity of consent more disputable in the cannibalism version of the case. Is disgust enhancing our ability to apply the law correctly in a case like this? It could be. But whoever supports such a theory should probably have the burden of proof. This position may be similar to one according to which racial biases – however odious as they may be in themselves – help in the correct assessment of the seriousness of certain crimes. The harsher punishments for black people are justified, while the milder punishments for white people are not.

In any case, even if disgust may function as a heuristic, the different response of the control group and the experimental group would point to an unsettling conclusion for the ideal of rule of law. Even if, paradoxically, disgust were to function as a heuristic rather than a bias, our experiment would demonstrate the existence of a phenomenon (the different susceptibility to disgust of the various decision-makers) that leads courts to apply the law differently in legally equivalent cases. This would be true whether being disgusted leads the decision-maker to apply the law more correctly or to apply it less correctly.

D. Your experiment is unable to mirror legal reasoning in a crucial respect: Real judges do not decide cases based on a single provision.

In our experiment, we do not ask subjects to provide the legal solution to complex cases, but simply to say whether or not a particular behaviour falls within the scope of a given rule. This could be seen as an oversimplification of the legal reasoning that judges and lawyers use in the courts. One answer to this objection is that, while it is true that legal reasoning requires the performance of various activities that this experiment does not allow us to study (in particular, the search for and selection of relevant norms from entire statutes, codes or case law), it is also true that it always and necessarily requires the mental process that this experiment is concerned with, namely the subsumption of concrete facts into abstract norms. If the experiment were successful, it would be easy to imagine variants of it aimed at testing whether ex post rationalisation phenomena might also concern other aspects of legal reasoning, like the process of finding relevant provisions or the reconstruction of facts through evidence.

VII. Conclusions

In this article, we have attempted to illustrate a way of dealing empirically with some questions that philosophy of law has traditionally studied in a purely speculative way. By adapting the methodology used by Johanthan Haidt in his experiments on moral psychology, it is possible to study the ability of rules to constrain the decision-making power of judges, and thus to test the possibility of putting the value of the rule of law into practice. An experiment such as the one described here does not, of course, have the ambition to shed definitive light on such a controversial and relevant issue. It does, however, have the ambition to show a direction in which research on the rule of law could be fruitfully developed, doing our part in countering the prejudice of considering the philosophy of law and experimental psychology as subjects with different objects and incompatible methodologies. In doing so, we follow the general line of experimental jurisprudence (see for an overview Tobia, 2022). Our specific contribution is to explore whether legal reasoning is similar to moral reasoning as described by Haidt and, based on an adaptation of Haidt’s methodology, to discuss whether legal rules can function as exclusionary reasons, given how they are processed by our minds.

If the experimental group tends to sanction the described behaviour more oλen than the control group, without citing the disgusting nature of the behaviour as a basis for the decision, this would imply that rules have a limited effect on our behaviour. This would be true, as we argued, whether disgust distorts or enhances legal reasoning. Moreover, if the two groups decided cases in substantially different ways, but no explanation emerged from the motivations offered by them in the dedicated section of the questionnaire, we would have reason to believe that legal reasoning, like moral reasoning, tends to be confabulatory in nature. This, on a descriptive level, would confirm certain traditional concerns of legal realism and, on a practical level, open the way for possible research into debiasing techniques that could be used to bring the behaviour of judges closer to constitutionalism’s aspirations of legality. If, on the other hand, no differences were found in the two groups, this will mean, if we accept on Haidt’s results on moral dumbfounding, that legal reasoning and moral reasoning function differently, a result that would make an interesting contribution to the philosophical debate about the distinction between law and morality. Subsequent experiments could be conducted to assess whether the expertise factor plays a role in the subjects’ ability to be guided by the rules rather than their own unconscious feelings. It is possible that greater legal training makes subjects more impartial, that lawyers tend to apply the law with a certain technical detachment that lay people do not have. On the other hand, it is also possible that legal expertise translates into a greater ability to invent specious arguments to justify one’s gut feelings.

The research could then develop in various directions. In all likelihood, some cases will work better than others in triggering condemnation, and the question will arise as to why this is so. Which disgusting but legally irrelevant aspects of the case have an impact on the reasoning? Why these and not others? Does the ex post rationalisation of a certain legal conclusion occur by distorting the reconstruction of the major premise of the practical syllogism (the question of law) or the minor premise (the question of fact)? It is probable that the decision-maker’s confirmation bias leads him or her to defend the conclusion in fact or in law quite indifferently, but it is also possible that there is a preference in one direction or the other. Take the soup case. Disgust with insects will either lead the decision maker to modify his notion of “harm” so as to include evanescent or symbolic injury in it (by appealing to vague terms such as dignity or respect) or to retain the notion of harm he would use even when not influenced by disgust but believing it more likely to be established in fact in the concrete case than he would otherwise (by unconsciously reversing the burden of proof or lowering the standard of proof otherwise required). Understanding at what level the bias operates can be crucial for studying institutional design strategies or procedural innovations that can avoid it.

References

Alexy, Robert, 1978: Theorie der juristischen Argumentation. Suhrkamp Verlag, Frank furt am Main.

Bobbio, Norberto, 1984: “Governo degli uomini o governo delle leggi?”, in Id., Il futuro della democrazia. Torino, Einaudi, pp. 157-180.

Bublitz, Christoph, 2021: “Rights as Rationalization? Psychological Debunking of Beliefs about Human Rights”. Legal Theοry, vol. 27, n. 2, pp. 97-125.

Celano, Bruno, 2021: Lezioni di filosofia del diritto. Costituzionalismo, stato di diritto, codificazione, diritto naturale, positivismo giuridico. Seconda edizione, ampliata. Torino, Giappichelli.

Churchland, Patricia, 2011: Braintrust. What Neuroscience Tells Us about Morality.Princeton, Princeton University Press.

Dworkin, Ronald, 1977: Taking Rights Seriously. Harvard University Press, Cambridge – Massachusetts.

Fuller, Lon L., 1964: The Mοralίsy οf Law. New Haven, Yale University Press.

Gigerenzer, Gert, 2008: Rationality for Mortals: How People Cope with Uncertainty. Oxford, Oxford University Press.

Greene, Joshua D., 2007: “The Secret Joke of Kant’s Soul”, in Walter Sinnott-Arm strong (ed.), Moral Psychology, Vol. 3: The Neuroscience of Morality: Emotion, Di sease, and Development. Cambridge (Mass.), MIT Press, pp. 35-80.

____________, 2014: “Beyond Point-and-Shoot Morality: Why Cognitive (Neuro)Science Matters for Ethics”. Ethics, vol. 124, n. 4, pp. 695-726

Gur, Noam, 2018. Legal Directives and Practical Reasons. Oxford - New York, Oxford University Press

Haidt, Jonathan, 2001: “The Emotional Dog and Its Rational Tail: A Social Intuitionist Approach to Moral Judgment”. Psychological Review, vol. 108, n. 4, pp. 814-834.

____________, 2012: The Righteous Mind. Why Good People Are Divided by Politics and Religion. London, Penguin Books.

Haidt, Jonathan and Matthew A. Hersh, 2001: “Sexual Morality: The Culture and Emotions of Conservatives and Liberal”. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, vol. 31, n. 1, pp. 191-221.

Haidt, Jonathan, Silvia H. Koller and Maria G. Dias 1993. “Affect, Culture, and Mora lity, or Is It Wrong to Eat Your Dog?”. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, vol. 65, n. 4, pp. 613-628.

Hart, Herbert L.A., 1958: “Positivism and Separation of Law and Morals”. Harvard Law Review, vol. 71, num. 4, pp. 593-629.

Hursthouse, Rosalind and Glen Pettigrove, 2023: “Virtue Ethics”, in Edward N. Zalta and Uri Nodelman (eds.), The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Fall 2023 Edition), https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2023/entries/ethics-virtue/ (30/03/2024).

Kahneman, Daniel, 2011: Thinking Fast and Slow. New York, Farrar, Straus and Giroux

Korma, Daniel Z., 2019: “Debunking Arguments”. Philosophy Compass, vol. 14, n.12, pp. 1-17.

Mallon, Ron and Shaun Nichols, 2010: “Rules”, in Doris, John M. and the Moral Psy chology Research Group (eds.), The Moral Psychology Handbook. Oxford – New York, Oxford University Press, pp. 297-320.

Manes, Vittorio, 2005: Il principio di offensività nel diritto penale. Canone di politica cri minale, criterio ermeneutico, parametro di ragionevolezza, Torino, Giappichelli.

Maroney, Terry A., 2011: “The Persistent Cultural Script of Judicial Dispassion”. California Law Review, vol. 99, n. 2, pp. 629-682.

Nichols, Shaun, 2014: “Process Debunking and Ethics”. Ethίcs, vol. 124, n. 4, pp. 727-749.

Nussbaum, Martha C., 2004: Hiding from Humanity. Disgust, Shame and the Law. Princeton and Oxford, Princeton University Press.

Patrick, Carlton and Debra Lieberman, 2018: “How Disgust Becomes Law”, in Stroh minger, Nina and Victor Kumar (eds.), The Moral Psychology of Disgust. London – New York, Rowman and Littlefield, pp. 121-134.

Radbruch, Gustav, 1946: “Gesetzliche Unrecht und übergesetzliches Recht”. Süddeussche Juristen-Zeitung, vol. 1, n. 5, pp. 105-108.

Raz, Joseph, 1986: The Morality of Freedom. Oxford – New York, Oxford University Press.

____________, 1990 [1975]: Practical Reasons and Norms. Oxford – New York, Oxford University Press.

____________, 2004: “Incorporation by Law”. Legal Theοry, vol. 10, pp. 1-17.

Ross, Alf, 1961: “Validity and the Conflict between Legal Positivism and Natu ral Law”. Revista Jurídica de Buenos Aires, vol. 4, pp. 46-93.

Richardson, Robert C., 2015: “Heuristics”, in R. Audi (ed.), The Cambridge Dictionary of Philosophy. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, p. 457.

Rozin, Paul, Jonathan Haidt, and Clark McCauley, 2008: “Disgust”, in Barrett, Lisa Feldman, Lewis, Michael, Haviland-Jones, Jeannette M. (eds.), Handbook of emotions. New York – London, The Guilford Press, pp. 757-776.

Schauer, Frederick, 1991: Playing by the Rules: A Philosophical Examination of Ru le-Based Decision-Making in Law and in Life. Oxford – New York, Oxford Uni versity Press.

Shweder, Richard. A., Manamohan, Mahapatra, and Jean G., Miller, 1987: “Cultu re and Moral Development.”, in Kagan, Jerome and Lamb, Sharon (eds.), The Emergence of Morality in Young Children. Chicago, University of Chicago Press, pp. 1-83.

Smith, Michael, 1994: The Moral Problem. Malden – Oxford – Carlton, Blackwell Pu blishing

Sood, Avani, Mehta, and John M., Darley, 2012: “The Plasticity of Harms in the Service of Criminalization Goals”. California Law Review, vol. 100, n. 5, pp. 1313-1358.

Tobia, Kevin, 2022: “Experimental Jurisprudence”. University of Chicago Law Review, vol. 89, num. 3, pp. 735-802.

Turiel, Elliot., 1983: The Development of Social Knowledge: Morality and Convention. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press

Turiel, Elliot, Melaine Killen, and Charles C. Helwig, 1987: “Morality: Its Structure, Function, and Vagaries.”, in Kagan, Jerome and Lamb, Sharon (eds.), The Emergence of Morality in Young Children. Chicago, University of Chicago Press, pp. 155-243.

Tybur, Joshua M., Debra, Lieberman, Robert, Kurzban R., and Peter, DeScioli, 2013: “Disgust: Evolved Function and Structure”. Psychological Review, vol. 120, n. 1,

Waldron, Jeremy, 2016: “The Rule of law”, in Edward N. Zalta and Uri Nodelman (eds.), The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Fall 2023 Edition), https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2023/entries/rule-of-law/ (05/04/2024).